This article is part of our series on Chinese American History. Sign up for our newsletter to receive family-friendly activity, recipe and craft ideas throughout the year!

Growing up during the 1980s, I wasn’t taught in school about the contributions made by Chinese immigrants during the course of American history. It’s only been in recent years that I’ve come to appreciate the importance of that omission.

If American culture is a shared set of experiences and traditions, then teaching the Chinese community’s history weaves its people and stories into the country’s social fabric. To feel included themselves, it’s important for Chinese American kids (and their classmates) to hear these stories included in the classroom, too.

To me, this pursuit of “inclusion” is a powerful theme throughout Chinese American history. The Chinese experience in America is a story of great determination and achievement, in the face of persistent efforts to pit diversity against class and exclude the Chinese from mainstream America.

I created this simple starter guide in case you want to share more information about the Chinese experience in America with your family or friends. Perhaps it will jump start a dinner conversation, provide extra context during a family vacation or fill in a gap from school.

Though it’s a fairly impossible task, I’ve organized nearly 200 years of Chinese American history into five short sections below, with links provided for further exploration. With enough retelling, hopefully we’ll take a few more steps toward making Chinese American history simply American history.

I. The Gold Rush

The discovery of gold in California in 1848 kicks off the first major wave of Chinese immigration to the United States. The Chinese introduce superior methods that improve the productivity of existing mines and reopen claims abandoned by other miners. Beginning in 1862, thousands of Chinese contribute their labor and ingenuity to construct the Transcontinental Railroad, despite inferior wages and work conditions. Following the railroad’s completion in 1869, Chinese workers are excluded from the closing ceremonies and are laid off without even return passage to California.

1848. Gold is discovered at Sutter’s Mill near Coloma, California.

1849. The first Chinatown in the United States is established in San Francisco, California.

1850s. The Chinese introduce the rocker, the waterwheel and the bucket-pulley system to the California gold fields.

1862. The Central Pacific Railroad is awarded the contract to lay tracks for the Transcontinental Railroad eastward from California.

1867. Two thousand Chinese rail workers organize to demand more pay and better working conditions.

1868. Hungry for railroad labor, the U.S. government signs the Burlingame Treaty with China, opening the door for “free migration and emigration” from China.

1869. Chinese rail workers set a new record by completing more than 10 miles of track in a single day.

1869. The Transcontinental Railroad is completed at Promontory Point, Utah. Laid off rail workers disperse across the nation in search of work.

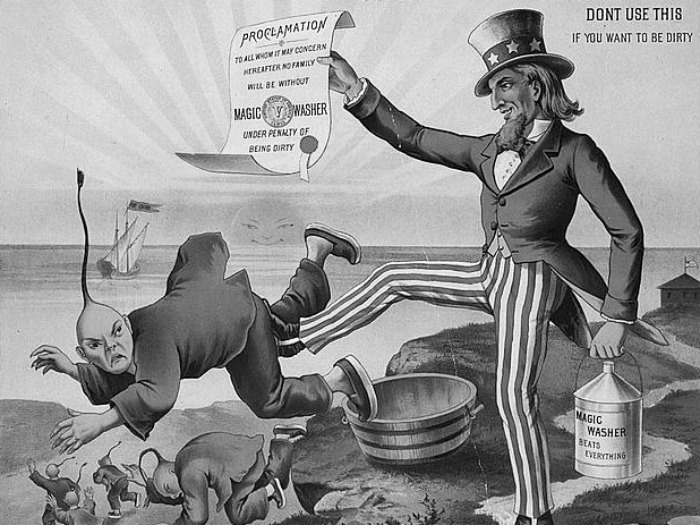

II. The Road to Exclusion

The Chinese community confronts economic depression and ethnic scapegoating during the 1870s. While former rail workers canvas the country for jobs, other Chinese become laborers and reclaim the vast Sacramento-San Joaquin delta for farming. Presaged by earlier California laws levying taxes on Chinese miners and preventing Chinese from testifying against whites in court, Congress withholds the right of naturalization, declaring the Chinese ineligible for citizenship. Populist leaders like Denis Kearney blame the Chinese for scarce jobs and low wages. Finally, on May 6, 1882, President Chester Arthur signs the Chinese Exclusion Act, barring new Chinese laborers from the United States.

1852. The California legislature enacts two new taxes, discouraging Chinese from coming to the United States and penalizing those already working in the gold mines.

1853. In People v. Hall, the California state supreme court bars Chinese from testifying against whites in court.

1870. Chinese workers are hired to break strikes at a shoe factory in North Adams, Massachusetts, and at a steam laundry in Belleville, New Jersey.

1879. Former president Ulysses S. Grant meets with Chinese officials to discuss a possible three- to five-year ban on Chinese immigration to the United States.

1882. President Chester Arthur signs the Chinese Exclusion Act, barring new Chinese laborers from the United States. This remains the only U.S. law ever to prevent immigration and naturalization on the basis of race.

III. The Exclusion Era

The Chinese Exclusion Act formalizes a period of systemic anti-Chinese discrimination. Legislation revokes Chinese reentry privileges, requires the registration of Chinese laborers and denies Chinese access to the courts for immigration matters. The Chinese win an important civil rights case, however, when the Supreme Court’s 1898 Wong Kim Ark decision affirms that all children born in the United States are American citizens. After the 1906 San Francisco earthquake destroys most of the city’s citizenship records, thousands of “paper sons” will enter the country through Angel Island. Though their parents are consigned to restaurant, laundry and grocery work by persistent racism, these Chinese American children begin to rise by pursuing education and professional skills.

1888. The Scott Act cancels the reentry privileges of all Chinese, stranding more than 20,000 people outside the country.

1892. The Geary Act requires all Chinese laborers in the United States to register with the government.

1898. The Supreme Court case of Wong Kim Ark affirms the 14th Amendment, declaring that all children born in the United States are American citizens.

1905. In United States v. Ju Toy, the Supreme Court denies Chinese immigrants access to the courts in immigration matters.

1906. An earthquake levels San Francisco, destroying the city’s citizenship records and opening the “paper sons” period.

1910. The government opens Angel Island in San Francisco Bay which will process more than 175,000 Chinese immigrants over the next 30 years.

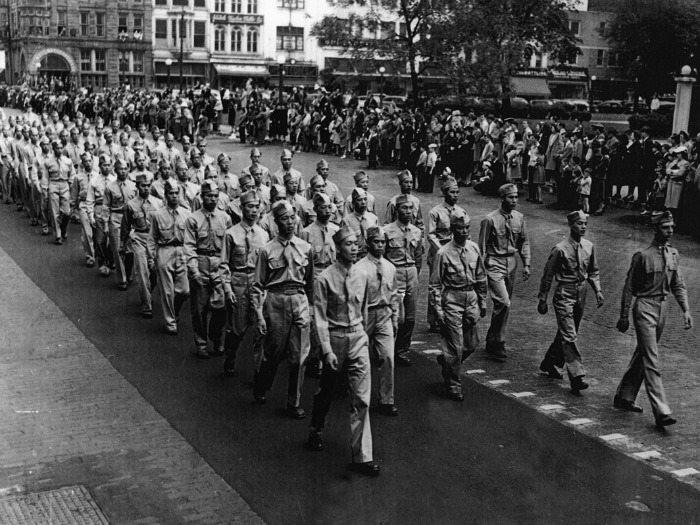

IV. Post World War II

World War II brings the United States out of the Great Depression and sends 20,000 Chinese Americans overseas to fight. The War Brides Act, authorizing Chinese American veterans to bring wives and fiancées to America, and post-war baby boom cause the size of the Chinese American community to surpass 100,000. Despite these advances, the Communist revolution in China throws new suspicions onto the Chinese American community and discrimination persists. Finally, on October 3, 1965, President Lyndon Johnson signs the Immigration and Nationality Act, allowing large-scale Chinese immigration to the United States for the first time in over 80 years.

1941. World War II sends 20,000 Chinese Americans overseas to fight.

1943. The Chinese Exclusion Act is repealed, but Chinese immigration remains limited to 105 per year.

1945. The War Brides Act permits Chinese Americans to marry in China and bring their wives to the United States by December 30, 1949.

1948. The Supreme Court rules unconstitutional the real estate covenants barring the sale of property to Chinese or other minorities.

1949. The Communist revolution in China throws new suspicions onto the Chinese American community.

1965. President Lyndon Johnson signs the Immigration and Nationality Act, abolishing racial discrimination in immigration law.

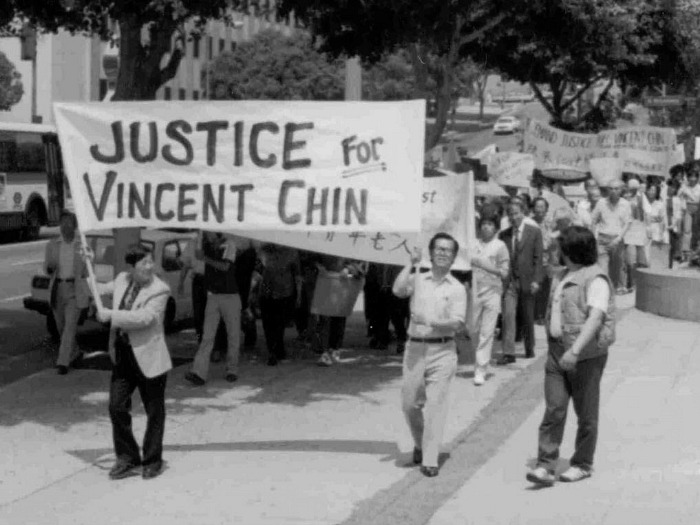

V. China’s Reopening and the Modern Era

President Richard Nixon’s 1972 visit to China marks the beginning of a 30-year surge in emigration from mainland China, Taiwan and Hong Kong. While a new generation of laborers replenishes Chinatown communities, this latest wave of immigrants includes scores of intellectuals, scholars and professionals who settle in American college towns and suburbs. Generalized as an upwardly-mobile “model minority” of high achievers, contemporary Chinese Americans remain underrepresented in mainstream popular culture, politics and business leadership.

1972. President Richard Nixon becomes the first American president to visit the People’s Republic of China.

1982. Vincent Chin is beaten to death in Detroit, Michigan, by two disgruntled autoworkers who mistake him for Japanese.

1989. Chinese troops put down the student pro-democracy protests in Tiananmen Square, killing hundreds.

1994. Jerry Yang founds Yahoo!

2000. An espionage case against the scientist Wen Ho Lee is dismissed without any evidence of wrongdoing.

2016. Chris Rock reinforces the model minority myth at the Emmys and Jesse Watters mocks elderly Chinatown residents during a Fox News segment.

Your turn! How does your family talk about Chinese American history? What other defining moments would you add to this article? I’d love to hear from you in the comments section below!

HT: Photos by Asia Society, Oakland Museum of California, Library of Congress, Huffington Post, NBC News and Advancing Justice.

Sarah Shim

Very interesting. In Hawaii our history of the immigration of the Chinese coming to Hawaii to work on plantations is quite unique. Many Chinese who migrated over 200 years ago settled in a beautiful place call Kula, Maui. They took advantage of the agricultural potential of the area. In the 1840’s they planted irish potatoes and shipped them to mining communities in California. By 1847 the farmers were very successful like the gold rush happening at the same time. Sun Yat-sen was a frequent visitor since his brother Sun Mei had a farm here in Kula. He was also educated in Hawaii so we add this bit of history to the Kula area. Hope you enjoyed this tidbit of history in Hawaii.

Wes Radez

Thank you for contributing that fascinating history, Sarah. The blending of cultures in Hawaii always inspires me. I’ll have to read more about Kula. ~Wes

Dave C

Another great article!

In keeping with Supreme Court theme. Two others come to mind Yick Wo in 1886 and The Slants much more recently in 2017.

Wes Radez

Terrific! I had been familiar with the Yick Wo case, but The Slants case in 2017 is new to me. Thanks for that! ~Wes

Roger S Dong

Please note that the 1945 War Brides Act authorized Chinese American VETERANS to marry and bring wives and fiancés to America.

Roger S Dong, Chair, Chinese American Heroes

Wes Radez

Thanks for writing, Roger. I’ve made that update! ~Wes